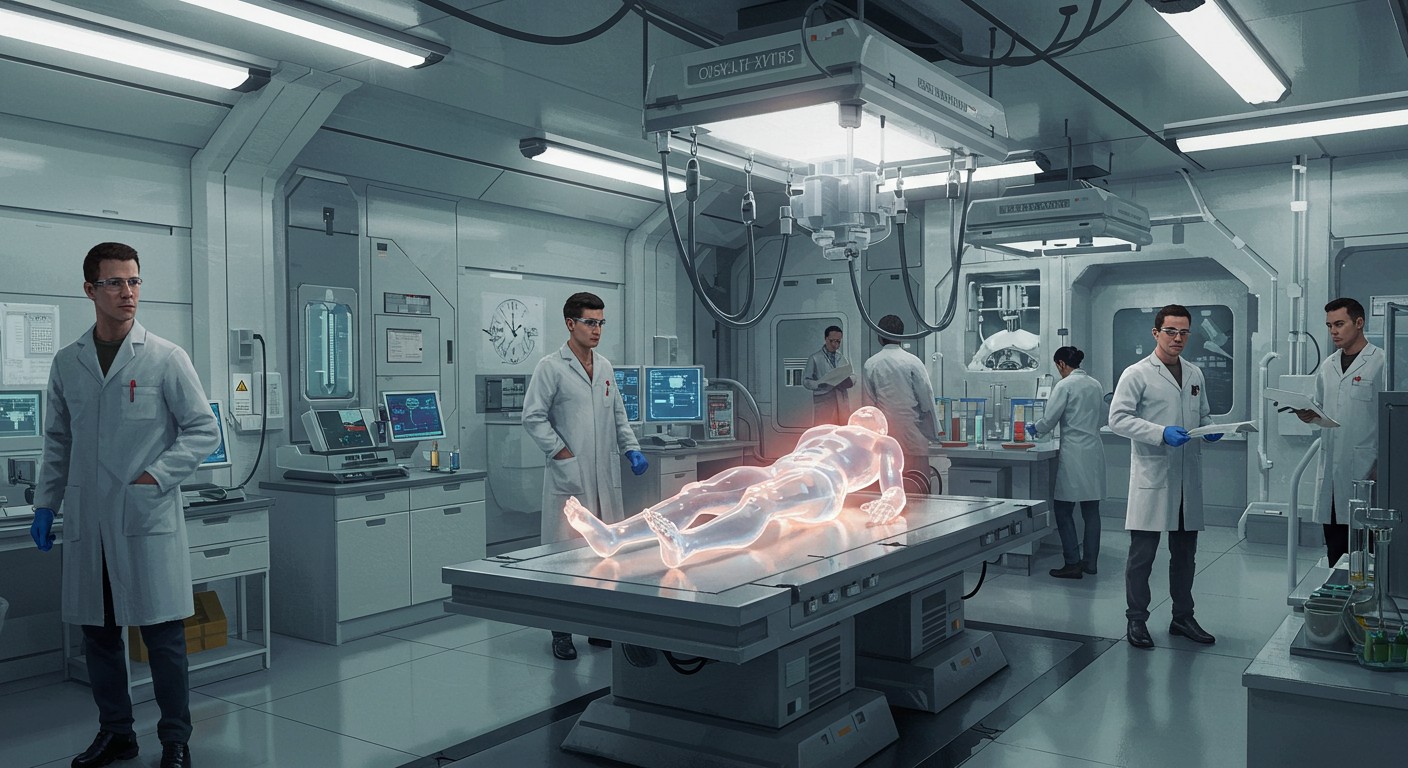

Imagine a world where scientists could grow human bodies—living, breathing, but without a brain or consciousness. Sounds like something straight out of a sci-fi flick, right? Yet, this isn’t just a plot twist from a late-night horror movie; it’s a real possibility being debated in labs and ethics boards today. The concept of bodyoids—genetically engineered human-like entities without neural capacity—raises questions that cut to the core of what it means to be human. I’ve always found the intersection of science and morality fascinating, but this topic? It’s a whole new level of mind-bending.

The Rise of Bodyoids: Science or Sci-Fi?

Let’s get one thing straight: we’re not quite there yet. Creating a fully functional bodyoid—a human body stripped of its brain and consciousness—remains a theoretical leap. But recent breakthroughs in stem cell research, gene editing, and even artificial uteruses are bringing us closer than you might think. Scientists argue these entities could revolutionize medicine, offering a limitless supply of organs for transplants or test subjects for drugs without the ethical baggage of harming sentient beings. But here’s the rub: is it really that simple?

The idea is to use stem cells to grow a human-like body that’s biologically functional but lacks the neural wiring for thought, pain, or awareness. Think of it as a living mannequin—human in form, but not in spirit. Researchers claim this could solve some of medicine’s biggest challenges, like organ shortages or the ethical issues of animal testing. But I can’t help wondering: are we opening a Pandora’s box we’re not ready to handle?

What Exactly Are Bodyoids?

Bodyoids aren’t your average lab creation. They’re not embryos, not robots, and definitely not zombies—at least, not in the Hollywood sense. They’re envisioned as human bodies engineered from stem cells, designed to lack a brain or nervous system. The goal? A living entity that’s human enough to serve as a biological resource but not human enough to raise moral red flags. Or so the theory goes.

Bodyoids could provide an ethically sourced supply of human-like material for medical research, bypassing the pain and suffering of animal testing.

– Biomedical researcher

But here’s where it gets murky. These entities would be grown in labs, potentially even implanted in a human womb via IVF techniques. The thought of a human mother carrying a brainless bodyoid feels, frankly, a bit grotesque. Even the researchers pushing this idea seem to shy away from that scenario, favoring artificial uteruses instead. It’s as if they know the optics are… unsettling, to say the least.

The Ethical Tightrope: Are Bodyoids Really “Ethical”?

Proponents of bodyoids argue they’re a game-changer for ethics in medicine. Why test drugs on animals that can feel pain when you could use a nonsentient human-like body instead? Why struggle with organ shortages when you could harvest hearts, livers, or kidneys from a lab-grown entity? It sounds like a win-win, but I’m not so sure.

For one, the assumption that bodyoids lack consciousness isn’t ironclad. We don’t fully understand consciousness—philosophers and neuroscientists have been at it for centuries with no clear answer. What if these entities have some rudimentary awareness we can’t detect? Plus, there’s the slippery slope: if we start creating human bodies for spare parts, what’s to stop us from dehumanizing other vulnerable groups, like those in comas or with severe disabilities?

- Organ harvesting: Bodyoids could provide a steady supply of organs, potentially saving millions of lives.

- Drug testing: They could serve as human-like test subjects, reducing reliance on animals.

- Ethical concerns: The risk of dehumanizing living beings with limited or no consciousness looms large.

Zombies, Animated Cadavers, and Brain Death

If bodyoids sound like something out of a zombie flick, you’re not wrong. The concept echoes the folklore of zonbi—mindless beings reanimated to serve as slaves. In modern medicine, we’ve already flirted with this idea through the concept of brain death. Since the 1960s, brain death—defined as the total loss of brain function—has been used to declare someone legally dead, even if their body keeps functioning with mechanical support. This paved the way for organ transplants, but it’s not without controversy.

Here’s the kicker: a “brain-dead” body isn’t entirely dead. It can breathe, circulate blood, heal wounds, and even gestate a baby. I read about a case where a brain-dead woman carried a pregnancy to term—how do you call that “dead”? Yet, we treat these bodies as resources, harvesting their organs while the heart still beats. Bodyoids take this a step further, creating entities designed to be brainless from the start. It’s like we’re engineering our own moral gray zone.

The line between life and death isn’t as clear as we’d like to think. Bodyoids blur it even further.

– Medical ethicist

The Slippery Slope of Dehumanization

One of the biggest risks of bodyoids is their potential to erode our sense of what makes us human. If we start viewing these entities as “less than” because they lack consciousness, what does that say about people with severe neurological conditions? Babies born with anencephaly, for example, lack a cerebral cortex but are undeniably human. Would bodyoids make it easier to dismiss their humanity, too?

I can’t shake the feeling that creating life solely to exploit it—whether for organs, experiments, or even food production (yep, some suggest animal bodyoids for meat)—chips away at our moral core. It’s not just about the science; it’s about what we’re willing to accept as a society. Are we okay with creating beings that are human in every way except the one that “matters”? And who gets to decide what matters?

| Entity | Consciousness | Ethical Status |

| Human | Full | Protected |

| Bodyoid | None | Unclear |

| Brain-dead patient | None | Contested |

What’s Love Got to Do With It?

You might be wondering why this article is categorized under Couple Life. At first glance, bodyoids seem far removed from relationships, but hear me out. The way we treat the most vulnerable—whether it’s a brain-dead patient, a bodyoid, or a person with profound disabilities—reflects the values we bring to our relationships. If we’re willing to exploit a human-like entity for science, what does that say about our capacity for empathy, respect, and love in our personal lives?

In relationships, we often face ethical dilemmas—how much to sacrifice, how to balance self-interest with care for another. Bodyoids force us to confront similar questions on a societal scale. If we create beings to serve us without regard for their potential humanity, are we eroding the very qualities that make relationships meaningful? I think there’s a connection worth exploring here.

The Future of Bodyoids: Hope or Horror?

Let’s be real: the science behind bodyoids is advancing faster than our ethical frameworks. We’re already creating embryoids—synthetic embryos that mimic early human development. These are typically destroyed after 14 days, but what happens when we push that timeline further? Could bodyoids become a reality in the next decade? And if they do, will we be ready to grapple with the consequences?

Some see bodyoids as a beacon of hope—a way to save lives through organ transplants or revolutionize medical research. Others, like me, can’t help but feel a chill at the thought of creating life only to strip it of its essence. It’s not just about what we can do; it’s about what we should do. And that’s a question science alone can’t answer.

So, where do we go from here? The debate over bodyoids isn’t just about science or ethics—it’s about who we are and who we want to be. I don’t have all the answers, but I know this: we need to tread carefully. The line between progress and peril is thinner than we think, and once we cross it, there’s no going back. What do you think—could bodyoids be the future of medicine, or are we flirting with a moral disaster?