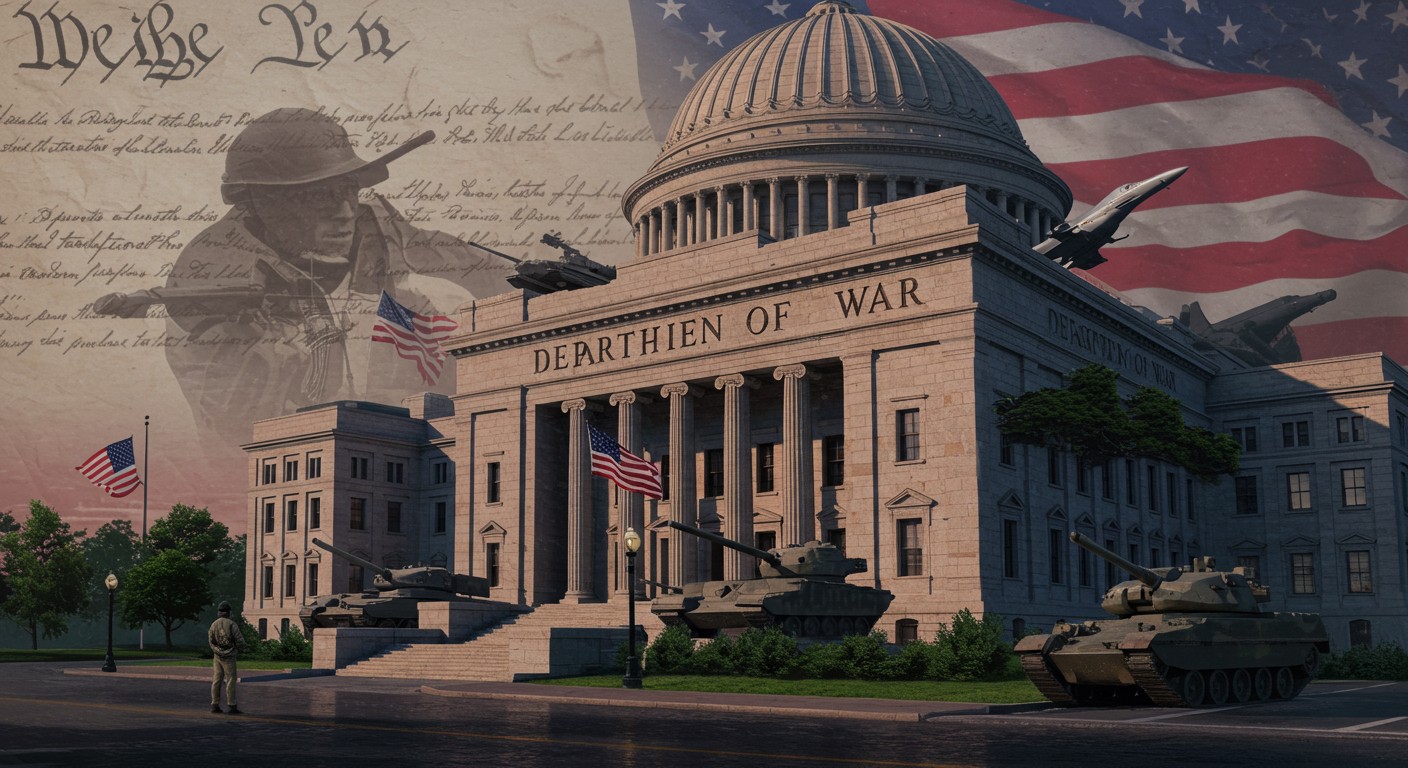

Have you ever stopped to think about what the names of government institutions really mean? The Department of Defense sounds like a protector, a shield against threats, right? But what if we called it the Department of War instead? The idea, recently floated by a prominent political figure, has sparked a firestorm of debate. It’s a bold suggestion that forces us to confront the reality of what our military does—and whether its current name is just a polite facade. In my view, there’s something refreshingly honest about stripping away the euphemisms, but it also raises big questions about how we approach conflict and power on a global stage.

The Case for Renaming: Clarity Over Euphemism

The proposal to revert the Department of Defense to its original name, the Department of War, isn’t just about semantics. It’s about truth in labeling. Established in 1947 under the National Security Act, the current name suggests a focus on protection, on safeguarding the nation. But let’s be real: the U.S. has been engaged in near-constant conflict since World War II, from Korea to Afghanistan to drone strikes in the Middle East. Does “defense” really capture what’s going on?

Renaming it could cut through the fog. A War Department implies action, aggression, and intent—not just reacting to threats but actively shaping the global landscape. Some argue this clarity could make policymakers and citizens alike rethink the costs and consequences of military engagement. As one expert put it:

Calling it a War Department forces us to own what we’re doing. It’s not just defense—it’s power projection.

– Policy analyst

But here’s where I pause. Would a tougher name make war feel more inevitable? Could it embolden leaders to flex military muscle without enough restraint? That’s the tightrope we’re walking.

A Historical Perspective: What’s in a Name?

Before 1947, the U.S. had a War Department, dating back to 1789. Back then, the name reflected a straightforward reality: the department managed wars, and wars were declared by Congress, as the Constitution demands. Those were different times, with clearer beginnings and ends to conflicts. Think of World War I or II—defined goals, clear victories. Compare that to today’s endless engagements, like the 20-year slog in Afghanistan. The shift to “Defense” came with the rise of the national security state, a term that encompasses the CIA, NSA, and a sprawling military-industrial complex.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the change:

- Pre-1947 War Department: Focused on executing declared wars, with Congressional oversight.

- Post-1947 Defense Department: Manages ongoing global operations, often without formal declarations.

- Key Difference: The modern setup prioritizes constant readiness over specific, limited conflicts.

In my experience, names shape perceptions. Calling something “defense” lets us sleep better at night, but it might also obscure the human and financial toll of perpetual war.

The Risks of a War Department

Let’s not kid ourselves—renaming the Department of Defense could have downsides. A War Department sounds aggressive, almost provocative. It might signal to the world that the U.S. is itching for a fight, which could escalate tensions with rivals like China or Russia. Imagine a diplomat from another country hearing “War Department” in a meeting. It’s not exactly a warm hug, is it?

Then there’s the domestic angle. A name change could normalize the idea of war, making it seem like the default rather than a last resort. One political commentator noted:

A War Department risks glorifying conflict over diplomacy. We need cooler heads, not hotter rhetoric.

– Foreign policy expert

I get it. Words matter, and “war” is a loaded term. It could shift public perception in ways that make peace harder to achieve. But there’s another side to this coin—maybe that’s exactly the wake-up call we need.

The Constitutional Argument: Back to Basics

Here’s where things get interesting. The push for a War Department could be paired with a return to Constitutional principles. The Constitution is clear: only Congress can declare war. Yet, since World War II, the U.S. has sidestepped this requirement, launching military actions through executive orders or vague “authorizations.” Korea, Vietnam, Iraq—the list goes on, and none had a formal declaration.

If we’re going to call it a War Department, let’s make it operate like one. That means:

- Congressional Approval: No military action without a formal declaration, except in cases of imminent attack.

- Clear Objectives: Define the mission, its scope, and its endgame before boots hit the ground.

- Accountability: Hold leaders responsible for the outcomes, not just the optics.

This approach could rein in the military-industrial complex, a term that’s thrown around a lot but carries real weight. It refers to the tangled web of defense contractors, lobbyists, and policymakers who profit from endless conflict. A War Department under strict Constitutional oversight might force us to rethink what we’re spending—and why.

The Budget Question: Defense or War Spending?

Let’s talk money. The U.S. defense budget for 2025 is projected to exceed $800 billion. That’s more than the next ten countries’ military budgets combined. But calling it a “defense” budget feels like a sleight of hand when so much goes to overseas bases, drone programs, and weapons development. A War Department would force us to call it what it is: a war budget.

Here’s a snapshot of where the money goes:

| Category | Percentage of Budget | Purpose |

| Weapons Development | 25% | Building advanced tech like drones and missiles |

| Overseas Bases | 15% | Maintaining global military presence |

| Personnel | 30% | Salaries, benefits for troops |

| Operations | 20% | Ongoing missions, training |

Renaming the budget to “war appropriations” might make taxpayers pause. Why are we spending billions on bases in Germany or Japan decades after World War II? What’s the return on investment for the average American? These are questions I’ve wrestled with, and I suspect many of you have too.

The Global Empire: Defense or Domination?

The U.S. maintains over 700 overseas military bases, a network often described as a global empire. Supporters say it’s necessary to deter threats and protect allies. Critics argue it’s about control—keeping other nations in check while securing economic interests like oil or trade routes. A War Department label might force us to confront this reality head-on.

Consider this: the U.S. has troops in over 150 countries. That’s not defense—it’s a global footprint. A War Department could push us to ask whether we’re defending freedom or projecting power. As one historian put it:

Empires don’t defend; they dominate. A War Department name might make that clearer.

– Military historian

Perhaps the most interesting aspect is how this could shift public debate. If we’re honest about the “war” part, we might start asking tougher questions about what we’re fighting for—and whether it’s worth it.

Why Winning Wars Matters

One argument for the rename is that the old War Department “won everything.” But that’s a oversimplification. Pre-1947 wars had clear objectives and Congressional backing, which made victories more achievable. Post-1947, the U.S. has struggled to “win” conflicts like Vietnam or Afghanistan because the goals were murky and the wars dragged on.

Here’s why the old system worked better:

- Defined Goals: Wars had specific aims, like defeating Germany in WWII.

- Public Support: Congressional declarations rallied the nation.

- End Points: Clear victories or treaties marked closure.

Today’s conflicts, by contrast, often lack these elements. A War Department could refocus us on winning by forcing clarity—provided we pair it with Constitutional discipline.

What’s Next for the Debate?

The idea of a War Department is a lightning rod. Some see it as a return to honesty, a way to stop hiding behind “defense” while waging wars. Others worry it could glorify conflict or alienate allies. I lean toward the former—it’s hard to fix a problem if you’re not honest about what it is. But the risks are real, and we’d need ironclad checks, like Congressional oversight, to keep things in balance.

So, what do you think? Would a War Department make us more accountable or just more bellicose? The answer might depend on whether we’re ready to face the mirror—and what we see when we do.

This debate isn’t going away anytime soon. It’s a chance to rethink not just a name but the principles behind it. Maybe it’s time to stop pretending we’re just defending and start owning what we’re doing—whatever that might be.